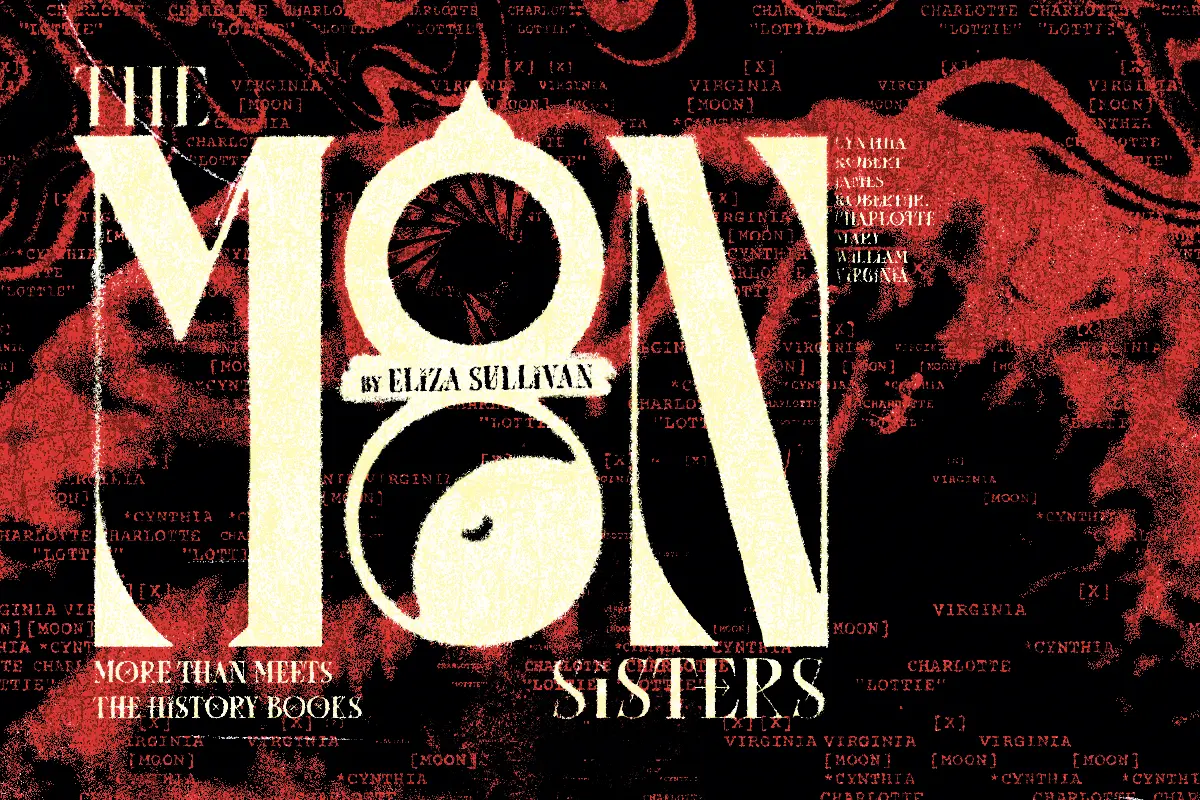

The Moon sisters

More than meets the history books

Eliza Sullivan

Hong Chuyen Nguyen

Who decides how history is told? Which details do we leave out? Which rumors do we leave in, allowing them to cement into fact? And how do we tell a complete story that shows people as they truly were?

When I set out to write this article, I wanted to report on an interesting historical tale from Oxford. However, once I chose my subjects — two sisters who served as Confederate spies — I was confronted with the reality that history is not always a perfect retelling of the past. Especially when few source materials are available, it can be difficult to fully understand a historical figure.

The Moon sisters’ stories have been muddled by rumor, retelling and conflation of different events. As such, I did my best to verify stories from multiple sources to distinguish fact from fiction. But the sources I found focused on the more fantastical elements of the sisters’ lives, painting them as heroines or folk legends and treating their allegiance to the Confederacy as a neutral fact.

I will first tell their story as it is presented by most sources: two enterprising young women crusading throughout the country on behalf of the Confederacy.

Early years in Oxford

The Moon family moved from Virginia, where they had owned slaves, to Oxford in 1833. They were staunch supporters of the Confederacy, perhaps in part because their family had been living in the South for generations. It is unclear why they moved to Ohio.

The family consisted of the mother, Cynthia, the father, Robert, and their children: James, Robert, Charlotte or “Lottie,” Mary, William and Virginia. Both Charlotte and Virginia were described as smart and rebellious young women. In their youth, they were said to have dressed up as boys to go climb trees with their brothers.

According to Miami University Professor Emeritus of History Curtis Ellison in his 2023 lecture, “Crossroad of Conflict — Oxford, Ohio and the American Civil War,” citizens of Oxford had mixed opinions regarding emancipation and civil rights at the time.

There were colonizationists who believed that slaves should be freed but then “removed from white society,” often by returning them to Africa. There were also Copperheads — Confederate sympathizers living in the North but working against the Union.

Some people were abolitionists who believed slaves should be freed and treated as equal members in society. Underground railroad routes ran through Oxford, and when war broke out, many Miami students volunteered as soldiers for the Union Army. Black political activists also lived in Oxford, most notably Hiram Revels, who later became the first Black member of Congress.

Lottie Moon

Lottie’s first name was actually Cynthia, but she went by her middle name, Charlotte, and was better known by her nickname, Lottie. She was born in 1828 in Danville, Virginia, and moved to Oxford with her family in 1833.

Lottie’s early life has been muddled by rumor. Even news articles written during her time were conflicting. The most famous rumor about her pertains to her relationship with Ambrose Burnside, an Indiana native who would later become a Union general and the namesake for sideburns. Allegedly, she and Burnside were engaged to be married, but on the day of the wedding, she got cold feet. When asked if she took Burnside as her husband, Lottie said “no-siree Bob” and ran out of the church.

The story of Burnside’s jilting at the altar was widely circulated, but its basis in fact seemed shaky; I was unable to find a firsthand account of the event. However, Burnside and Lottie almost certainly knew each other based on contemporaneous accounts of their contact during the war in newspapers, including The World and The Hamilton Telegraph.

Lottie ended up marrying a different man: James Clark, a Miami alumnus, prominent lawyer and leader of the Copperhead movement. According to an article from The Oxford News, on the day of the wedding, Clark brandished a pistol, told Lottie, “there will be a wedding here or there will be a funeral,” and led her to the altar.

Another account from The Hamilton Telegraph reported that one of Lottie’s other suitors was plotting to kill Clark on their wedding day, so Lottie brought a pistol to the wedding for protection. Regardless of the presence or absence of various firearms that day, the two were married, and Lottie Moon became Mrs. Clark.

Lottie’s most compelling story involved former President Abraham Lincoln himself. Lottie traveled to Canada to retrieve a message from Confederate sympathizers for Confederate President Jefferson Davis. But, to cross to the opposing territory, she needed permission from Washington, D.C.

Posing as a sick woman, Lottie requested permission to visit the hot springs in Virginia. While her paperwork was being processed, she met Secretary Edwin Stanton, who was deceived by her story. He was concerned for her condition and advocated for her to go south with Lincoln, who was traveling to a Union military base. As one of the president’s travel companions, she was allowed to cross into the South, where she remained for several months.

On her return voyage, still disguised, Lottie was detained in Winchester, Virginia, by General Robert Milroy. He was suspicious of her claims of illness and sent her to his chief surgeon for examination.

Lottie had a strange talent: She could convincingly unhinge her jaw, creating loud cracking noises and causing her to grimace in pain. When the doctor saw this, he was convinced she had rheumatism and that she should be allowed to continue to her destination unimpeded.

She likely continued to spy for the rest of the war, though specific details are difficult to find or verify.

After the war, Lottie and her husband had a son, Franklin Pickney Clark. She then became a reporter for The New York World newspaper before being sent to Europe to cover the Franco-Prussian War. After her return to the States, she wrote three books under the pen name Charles M. Clay. She died in 1895.

Lottie’s story has captivated many, including Miami’s own Walter Havighurst, who wrote an account of her meeting with General Burnside in his article “The Redemption of Lottie Moon.” Her story was also broadcast on a radio show in 1950, where she was voiced by Lucille Ball, a star actress best known for her leading role in the sitcom “I Love Lucy.”

Virginia Moon

Virginia, also called Ginnie, was born in Oxford in 1844. As a teenager, she was a staunch supporter of the South and a friend of Jefferson Davis. He wrote her at least one letter wishing her well during the war.

When the Civil War began in 1861, she was a student at the Oxford Female Institute, though she was soon expelled for shooting the school’s Union flag. In 1863, during a visit to Oxford, she scratched “Hurrah for Jeff Davis” into a shop’s window with her ring.

Virginia was described as a beautiful woman and was allegedly engaged to as many as 16 Confederate soldiers, saying, “If they died, they would die happy, and if they lived, I didn’t give a damn.”

The most dramatic story from Virginia’s time as a spy was cataloged in her unfinished memoir published by The World.

Virginia wrote that she was aboard a boat in a Cincinnati port, waiting to go to Memphis, Tennessee. She had quinine and morphine, two types of medicine badly needed by the Confederate Army, as well as secret letters sewn into her dress. The letters were from the Knights of the Golden Circle, a group of Confederate sympathizers working to establish a rebellion in the North. In her luggage was fabric to make shirts for Confederate soldiers and a ball of opium.

She and her mother were settling in for the journey when a Union soldier, Captain Thomas Rose, knocked on her door. He had a telegram ordering her arrest, claiming she was carrying contraband and rebel mail. He took her to the State Room and attempted to search her. Virginia knew she could be killed if he discovered the secret letters hidden in her clothing, so she pulled a pistol out of her dress and pointed it at him, saying, “If you make a move to touch me, I will kill you, so help me God.”

Rose suggested leaving the boat and going to the marshal’s office, where they could search her properly, and Virginia obliged. While waiting for a carriage to take her there, Virginia took the secret letters out of her dress, dunked them in water and swallowed them. She also left her underskirt, with the bottles of morphine and quinine sewn inside, with her mother, who was not arrested.

At the marshal’s office, Union soldiers searched her suitcase, where they found the shirtcloth and opium, and accused her of carrying contraband. Virginia asked to speak with Burnside, who was now a general for the Union and whom she knew from his relationship with her sister before the war.

Upon their meeting, Burnside had her court-martialed. She was exonerated of the charge of carrying contraband, but he still kept her under parole for three months.

After those three months, Virginia was allowed to return to Kentucky.

I was unable to find evidence of her specific activities after this incident, but she was later arrested by General Benjamin Butler in New Orleans and detained at Fort Monroe for several months, indicating that she was likely still engaged in espionage.

Near the end of the war, Virginia moved to Memphis, where she became renowned for her work raising money for charity, running a free boarding house and caring for yellow fever patients. She became known as a “one-woman charity fund.”

After the war, she became an actress, with her most famous role being the grandmother in the 1923 film “The Spanish Dancer.” She was living in New York City with her niece when she died in 1925.

The details we can’t forget

The story of the Moon family cannot be divorced from the historical perspective in which it stands. On one hand, the Moon sisters led fascinating lives and were forces for good in some aspects: Both women pushed the limits of what was acceptable for women to do in their time, and Virginia performed notable charity work during and after the Yellow Fever epidemic.

On the other hand, the women were risking their lives for the Confederacy. Based on newspaper accounts, both sisters continued their allegiance to the Confederacy until their death and fully supported the subjugation of Black people. Sources reporting on the Moon sisters’ stories do not acknowledge what being a Confederate spy really means; they do not acknowledge that the women were fighting for the continuation of slavery in America.

Sometimes, excuses are made that historical figures “didn’t know better,” so we can’t judge them by modern standards. This argument cannot be made for the Moon sisters: Many of their contemporaries understood the horrors of slavery and were fighting to abolish it.

Ellison said in his lecture that reporting on the Moon sisters has romanticized them. I agree with this assessment; none of the sources I found mentioned the problems with the sisters’ allegiance to the Confederacy, instead presenting it as a neutral fact.

While these women did some good things in their lives, it is important to remember that they devoted many years to the Confederacy, and they both retained that allegiance to the end of their lives.

I chose to tell their story not because they were good people or because they stood for a good cause, but because they led interesting lives. Moreover, the way their lives have been reframed through retellings that neutralize the issues of their time is an interesting case study in historiography and a good reminder of the burden we all bear to report the full truth, not just the salacious stories.

The research for this article is largely based on articles from The World, The Hamilton Telegraph and The Oxford News published between 1897 and 1923, which I found at the Oxford Lane Library’s Smith Library of Regional History. This information was cross-referenced with the book “Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others” by Larry G. Eggleston.