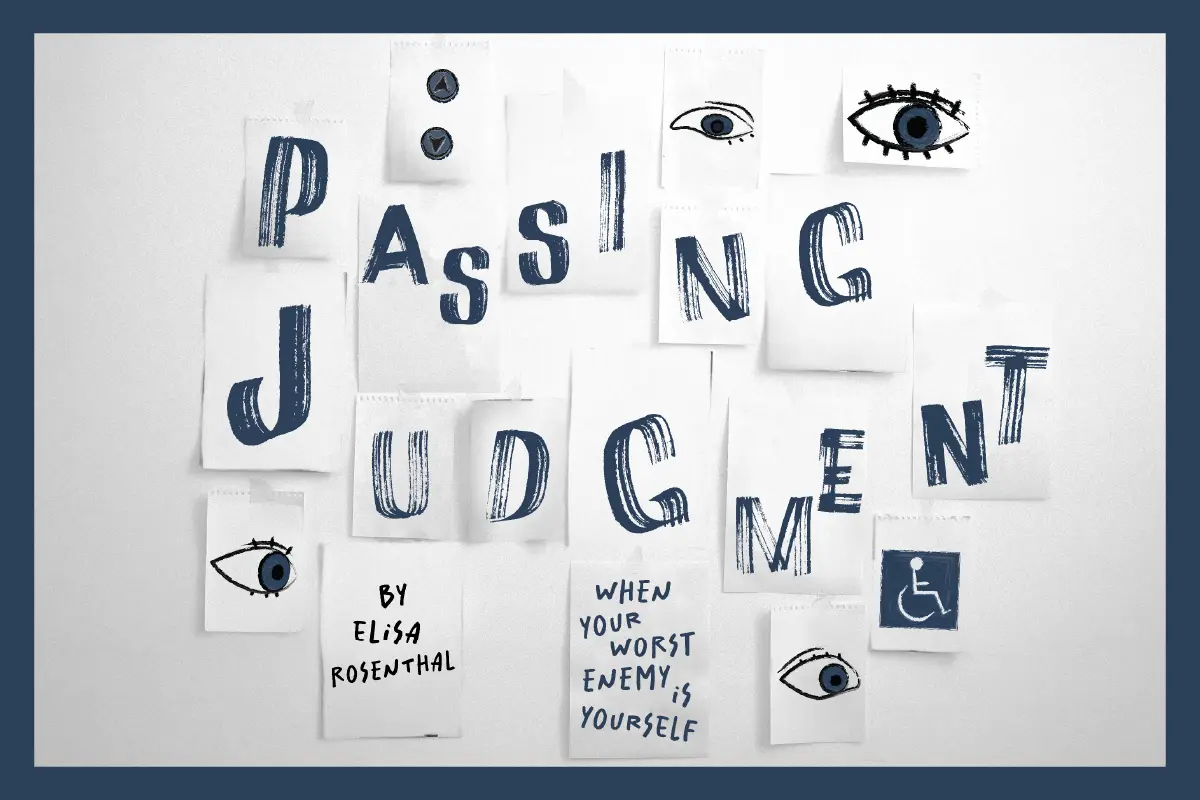

Passing judgment

When your worst enemy is yourself

Elisa Rosenthal

Madi Patton

Judgment is something people try to avoid, but we often end up guilty of it anyway. It’s human nature to make assumptions about others at first glance. Initially, several identifying characteristics of who I am aren’t apparent through visual cues alone. I’ve realized I can’t expect others to judge me correctly, so when I make my own judgments, I admit that I’m not always going to be right.

As someone who lives with an invisible disability, sometimes the fear of judgment is more intimidating than the reality of it. In the six years since my diagnosis, I’ve been judged and misjudged by everyone from doctors to family to strangers. It isn’t always negative, although the connotation feels that way. I’ve learned that the harshest critic lives in our own minds, and the easiest way to be free of judgment is to stop judging ourselves.

When I was 15, I got sick one week seemingly out of nowhere. While receiving intravenous fluids in the Children’s Hospital ER, a doctor told me I had the textbook symptoms for a chronic condition called Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS).

“What an ironically harmless-sounding name for a chronic illness,” I thought, sitting in my hospital bed at midnight on a Thursday evening in 2019.

A few days later, in a neurologist's office, the diagnosis was confirmed through a test where I stood with my arms in a T position and my eyes closed. As I bobbled and teetered, it proved my body couldn’t regulate my blood flow correctly, causing dizziness and balance issues.

As a teenager surrounded by other teens at the peak of social scrutiny, I told no one. I felt my identity revolved around being a dancer: Dancers have good balance, dancers can’t be disabled, so I can’t be disabled. If people knew what I was living with, my identity would have to change, a feat I wasn’t ready for.

So I told no one, avoided the conflict altogether, and lived my life as normal until I couldn't anymore. That day came on Jan. 22, 2020; I was feeling dizzy and felt like I couldn’t think, so I went to the nurse and went home.

Things have never truly been the same. It had been less than a year since that fateful ER visit, and not enough time had passed to accept this new part of who I was becoming.

My disability has become an unavoidable part of who I am, and for a long time, that was a tough pill to swallow, both literally and figuratively. My illness took over my life, and I could no longer get away with hiding it without hiding myself. So for a while, that’s what I did.

The COVID-19 quarantine was conveniently timed, allowing me to start healing and coping without having to show the world the new me. I hated who I was, hated being sick and wished desperately to go back to a version of myself I couldn’t be anymore.

People in my life didn’t look at me differently for the illness, but the thought that they could consumed me. I was fearful that everyone sensed me changing and didn’t like what they saw. The fear blinded me to the truth that my family and friends would love me unconditionally, no matter what level of ability or disability I possessed.

The word chronic hung over my head. I felt weak, so I became weak, subject to the control of an illness that I knew would never go away.

My judgment of myself became a self-fulfilling prophecy, and the things I feared became truths through the lens of my own subconsciously negative perceptions.

Over the years, my condition improved, and I realized overcoming tough situations was more telling than the times of suffering. My loved ones praised me for my strength and perseverance, and the phrase “God gives His toughest battles to His strongest soldiers” became a repeated mantra in many cards, texts and calls.

The turning point in my view of myself came when I realized that I was in control of only myself, not others. I put a higher value on doing what made me happy, regardless of who might judge me for it.

Now, I’m much more open to telling people about my disability as I realize it’s not a negative reflection of who I am. Instead, it tells a story of my resilience and how much I’ve overcome in my life, not letting it control me.

This past year, I got a handicap tag through one of my doctors, finally allowing me to utilize parking spaces to shop without fear of it taking a significant toll on my health. Standing for long periods of time can be a challenge, and I never know when symptomatic flares will hit.

The pass came with a newfound anxiety that others would question my credibility to use it or even be disabled in the first place. The world is full of mean people, and I was entirely convinced I would have to fend off an unbelieving stranger at one time or another. I was so sure that I thought up a retort in my head and practiced it every time I pulled into a blue-lined spot.

I imagined someone coming up to me, doubting my legitimacy to park in the space, telling me it's for disabled people only or asking if I was using someone else’s car. I’d reply by telling them not all disabilities are visible, and although I appear perfectly abled, I’m not, and judging me on first glance is harmful to me and the disabled community as a whole.

It’s been almost a year now, and despite a few strange glances, barely anyone has batted an eye at my usage of these spots. Sometimes, even the glances are just in my head, sending an unintentional message because of my own hypersensitivity to the situation.

My insecurity gets projected outward, pushing a nonexistent judgment of myself onto others, using resources I feel I had to earn. Every time I use an elevator, as I’m huddled around the doors with other students, I find myself wondering if they really need to use it or just didn’t want to take the stairs. The assumption I feel victimized by, I’m now using to villainize others.

I find myself thinking they look capable of using the stairs, or how lazy they must be to not want to walk up two flights. This type of thinking ignores others’ wants and needs, and I take the place of those who I feel criticized by when using handicap parking.

Realistically, it doesn’t matter as much who uses the elevator. You don’t need to be disabled to not want to hike your way up the dreaded McGuffey stairs, so why do I care? I let it interfere with my day and upset me, but I somehow expect others to do the opposite toward me.

It’s a double standard that I fall victim to daily without noticing, and I know it comes from insecurity about my identity and my level of ability.

Invisible disabilities create a strange gray area between able-bodied people and those who appear disabled in more obvious ways.

It took me years to accept the title of disabled and feel comfortable using resources I know are made for people like me. Seeing others use resources I felt I had to earn without thinking can be hard, but it’s not their fault I felt uncomfortable using them.

I often remind myself that judging others impacts me the most, and fighting that voice in my head making assumptions is a valuable skill in all realms of life. Learning to accept myself is a process, one that I’m still in and will be for the rest of my life. I’m still working on being less judgmental of myself, and judging others less will come with that. Growth isn’t linear: Everyone’s journey is different, and learning to understand that minimizes negative perceptions of those around you.